Hyperallergic

September 10, 2021

“Seeing the Armory Art Fair as a Chance to Reconnect”

By Seph Rodney

Seeing the Armory Art Fair as a Chance to Reconnect

While the Armory Show is a capitalist bacchanal, it’s also like an end-of-summer cookout, bringing parts of the art community together in celebration.

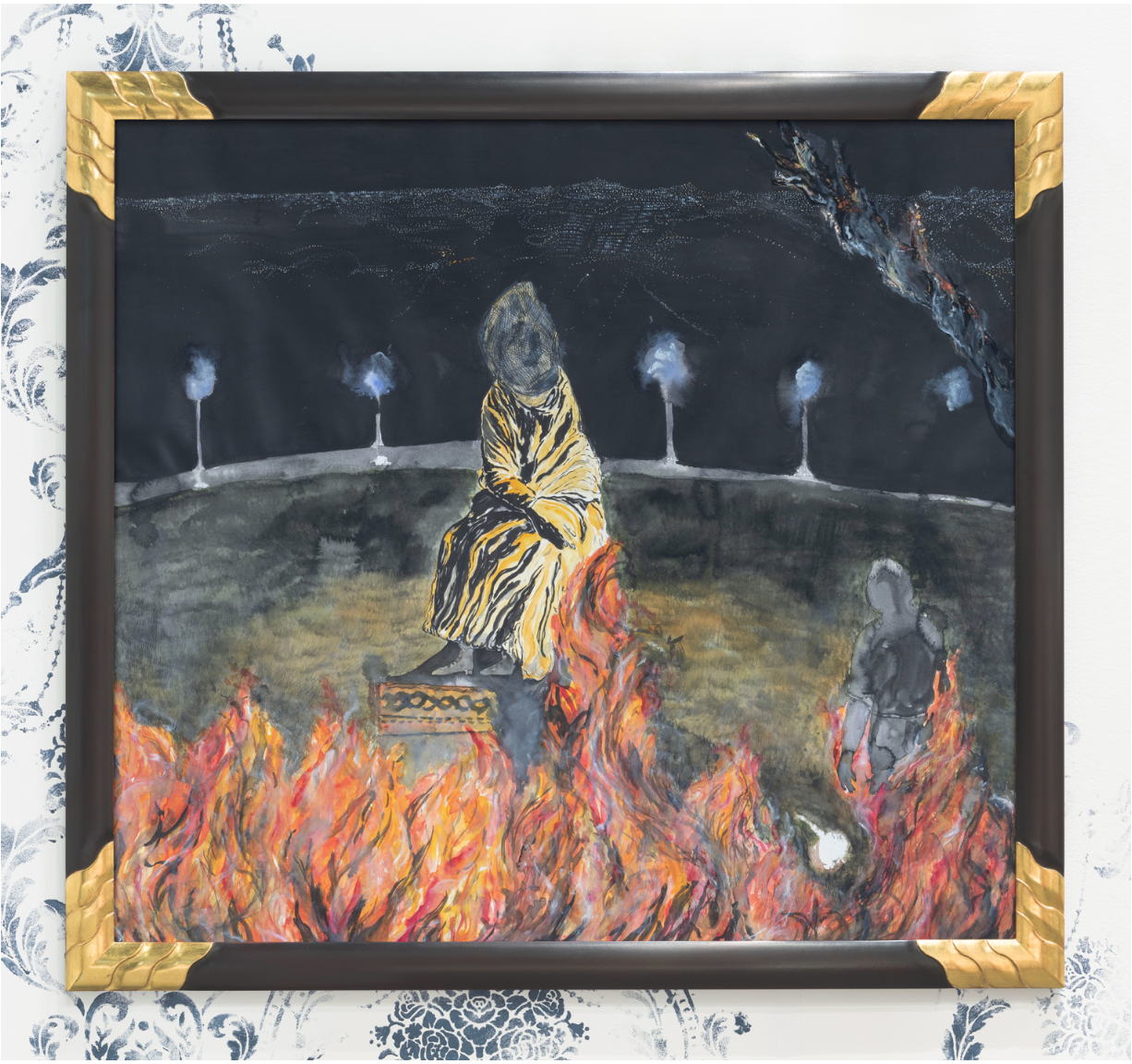

At Anna Zorina gallery, New York: Kambui Olujimi, “Canopy” (2021) watercolor on paper41.125 x 59.75 inches (all images by the author unless otherwise noted)

It is stating the obvious to say that the Armory Show is a capitalist bacchanal. What is also true about it, which isn’t necessarily obvious, is that it’s also like an end-of-summer cookout, bringing parts of the art community together in celebration. I get to see cousins I hadn’t seen in a long time and marvel at how they’ve grown. Perhaps I felt excited and happy to see many, many friends and colleagues because the pandemic has starved me of real human connection, but this feeling may also have to do with being in the arts community a few years and having developed genuine admiration for what some artists make and do. I was back at the Armory for the first time in three years, and admittedly initially went in with the attitude of “Okay, let’s get it over with.” But I kept running into artists, curators, critics, and gallerists in my community who I value and appreciate. So, another feeling emerged while trying to make sure I saw every booth and took pictures of all the art pieces that moved me: a kind of gratitude for being able to see and document the work. This time, I focused on the work that I’ve seen glimpses of in the year or years prior, the artists who I’ve written about or wanted to write about, but couldn’t quite find the time or space to do so. This fair trip also serves me as a preview for some of the shows I can already tell I want to cover more deeply in the coming months.

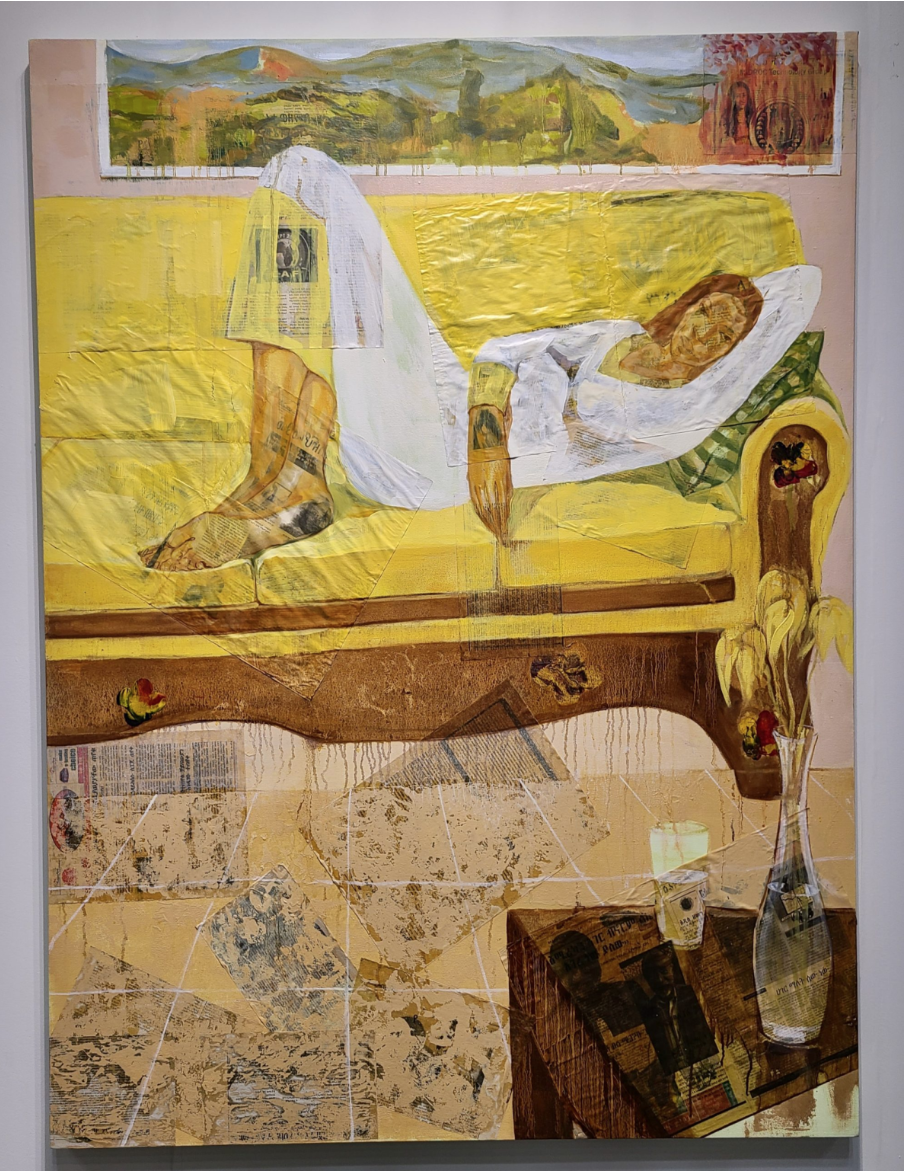

At James Fuentes, New York: Didier William, “Mosaic Pool, Miami” (2021) acrylic, oil, ink, collage, wood carving on panel paper, 63 x 106 inches

I especially enjoyed talking with Kambui Olujimi about the watercolor work that he showed at Anna Zorina gallery. I had seen a previous show of his at Project for Empty Space: an exhibition titled Walk With Me which contained about 200 ink-wash portraits on paper, all versions of an image of Catherine Arline, who had recently passed away and was described in the gallery text as “the artist’s longtime mentor, friend, and guardian angel.” I had wondered about the obsessiveness of those portraits, wondered how Olujimi would find a way to metabolize his grief and how long he would stay with it. He told me that project had him working with watercolors for three years and through that experience he got to the current work at Anna Zorina gallery: images of monuments either being unveiled or prepared for removal. The same washy, gauzy, somewhat expressionistic style carries over well and makes the statues seem like there are both ethereal and powerfully present.

At Anna Zorina gallery: Kambui Olujimi, “Late Stage Love Affairs” (2021) watercolor on paper 40.75 x 44.5 inches (image courtesy Anna Zorina gallery)

I reconnected with the work of Didier William who has shifted his paintings of figures who are meant to evade the colonizer’s gaze into more colorful versions that are now clothed against a floral background. These innovation make his figures seem to be part of a narrative that William is weaving over the course of an entire corpus of paintings. I was glad to again see Michael Rakowitz’s project of restaging the works lost within “Room H” located in the Northwest Palace of the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud. It’s such powerfully evocative work that I could see the work throughout my life, like a favored novel I can return to from time to time. I had wanted to write about Bony Ramirez’s strangely surreal portraits at Thierry Goldberg gallery. His figures with their distorted, elongated, and flattened limbs are a unique visual style for exploring the ways of being a human. I had felt similarly about seeing Arghavan Khosravi’s recent show at Rachel Uffner gallery. Khosravi has a way with using shaped panels and wood cutouts to add dimension and intrigue to her painted images that suggest a narrative I can only get bits and pieces of. And Hana Yilma Godine’s previous show at Fridman gallery I found ethereally beautiful and I had wanted to spend more time with her paintings.

At Jane Lombard gallery, NewYork: Michael Rakowitz, installation view (2021)”The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist (Room F, Section 1, Northwest Palace of Nimrud)”

At Rachel Uffner gallery, New York: Arghavan Khosravi, “Watching” (2021) acrylic on canvas over shaped panels, wood cutout and colored pencil 64 x 48 x 5 inches

I also was introduced to new artists. Adrienne Elise Tarver’s work was displayed by Ivy Jones, the director of Welancora gallery, a space I’ve visited a few times in the previous years because they have consistently strong shows. Frankly they deserve more attention than the gallery gets. Tarver’s textile work is mainly colorful portraits of women that gorgeously intricate and move toward the mystical. Housing gallery showed some lovely heavily stylized portraiture paintings by Nathaniel Oliver that meld figure and ground. For the galleries outside the United States, I was pleasantly surprised by Kwesi Botchway’s work at Gallery 1957 in Accra, Ghana. His portraits of Black people all with mottled obsidian skin tones and a bright pink lower lip are sumptuous visual meals. And lastly the portrait “Suspect #5” (2021) by Ludovic Nkoth, at the booth for Luce gallery in Turin, Italy, made me pause, then stop and marvel at his facility with paint. The face is all swirls and textured surfaces that yet cohere into a person.

At Welancora gallery, Brooklyn: Adrienne Elisa Tarver, “High Priestess” (2021) embroidery and woven textile, 50 x 36 inches

At Gallery 1957, Accra and London: Kwesi Botchway, “Fancy Pillows” (2021) acrylic and oil on canvas, 70 x 50 inches

At Welancora gallery, Brooklyn: Adrienne Elisa Tarver, “Temperance” (2021) embroidery and woven textile, 50 x 36 inches

Before the fair I had exchanged Twitter messages with a colleague who said she was confused about the people who had made vocal protestations about the need to change the art scene in the wake of the global pandemic and the issues that it brought to the surface (the environmental crises, the hegemony of the one percent, the systemic devaluation of Black lives) and then live-reported their art fair experiences. I understand the confusion, how art fairs always seem to privilege and fete consumptive behavior. But they do more than that for me. They give me an opportunity to reconnect, to revisit, to see an artist’s work and share the brilliance of my community, saying to the reader, “Look at what they’ve done. Isn’t this marvelous?”

At Thierry Goldberg gallery, NewYork: Bony Ramirez, “Del Mar Venimos” (2021) acrylic, color pencil, soft oil pastel, cowrie sea shells, dry coconut seed pod, Bristol paper on wood panel, 72 x 53 inches

At Housing gallery, New York: Nathaniel Oliver, “Slack Tie Dip” (2021) oil on canvas, 66 x 70 inches

At Fridman Gallery, New York: Hana Yilma Godine, “Spaces Within Space (1)” (2019) oil, acrylic, collage on canvas, 70 x 54 inches

At James Cohan gallery, New York: Alison Elizabeth Taylor, “Sketch for a Still Life” (2020) marquetry hybrid, 50 x 63 inches

At Robert Koch gallery, San Francisco: Adam Katseff, “River XVII” (2014/2021) lacquered pigment ink print, 59 x 73 inches image and mount

At Victoria Miro gallery, New York: Doron Langberg, “Willy” (2021) oil on linen, 96 x 80 inches

At Luce Gallery, Turin: Ludovic Nkoth, “Suspect #5” (2021) acrylic and sand on linen, 60 x 48 inches

The Armory Show continues through September 12 at the Javits Center (429 Eleventh Avenue, Hell’s Kitchen, Manhattan).